A Sermon by the Rev. Dr. Arthur M. Suggs

Preached on the Ninth Sunday after Pentecost, July 22, 2018

Lectionary Reading: Matthew 5: 21-26.

A Prayer, a Song and a Bible, Do They Mark Us Guilty of Murder and Adultery?

Several years ago, Richard Rohr and James Marchionada, both priests, one Franciscan and the other Dominican, were attending a memorial service in remembrance of the September 11 disaster. Richard Rohr wrote a prayer. James Marchionada wrote a song.

Here is the prayer:

“God of all races, nations, and religions,

You know that we cannot change others,

Nor can we change the past.

But we can change ourselves.

We can join you in changing our only

And common future where Love ‘reigns’

The same over all.

Help us not to say, “Lord, Lord” to any nationalist gods,

But to hear the One God of all the earth,

And to do God’s good thing for this One World.”

For the song, the refrain goes like this:

“It’s not up to God alone to listen to prayer.

It’s not up to God alone to answer.

But when the people of God become what we pray,

the kingdom of God is revealed.”

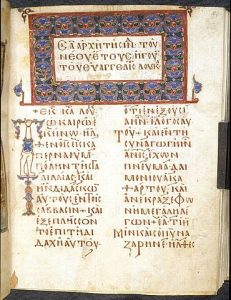

Then Julie Ann Johnson read a difficult passage from the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5: 21-22):

“You have heard that it was said to those of ancient times, ‘You shall not murder’; and ‘whoever murders shall be liable to judgement.’ But I say to you that if you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgement; and if you insult a brother or sister, you will be liable to the council; and if you say, ‘You fool,’ you will be liable to the hell of fire.”

In the next paragraph, Jesus goes on to say pretty much the same thing about adultery (Matthew 5: 27-28):

“You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall not commit adultery,’ But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart.”

Jimmy Carter isn’t the only one. He’s just the only one who has admitted it. According to this, we are all guilty of murder and adultery. Every last one of us!

Jesus Seems to Be Rather Loving and Forgiving, but What Is Going on Here?

There is only one way I can understand this, and it has to do with the way in which our thoughts precede our actions.

Jesus directly says that our inner attitudes and states are the real sources of our problems, heralding our outward behaviors. Most religion is obsessed with a small number of such potent activities, and we clergy think it is our job to disengage them.

This is largely a waste of God’s time and ours. Jesus says not only that you must not kill, but that you must not even harbor hateful thoughts and feelings (Matthew 5: 21-22).

He clearly begins with the necessity of a “pure heart” (Matthew 5: 8), a pure mind and conscience, knowing that the outer behavior will follow. It always does. Too often we force the external behavior, and the inner force remains fully operative within us like a cancer.

This explains why so many Christians are still racist, classist, sexist and homophobic, and are apparently proud of it.

I’m touching on politics this morning. Going on vacation very soon, so this seems like the right time.

I’m in a Predicament, Having Political Views Linked to Morality, yet I Speak of Spiritual Principles

A few things:

1. Everyone has their own political views.

2. Politics is inextricably linked to morality.

3. How do I prevent my personal views from leaking into our worship service?

4. The only solution I have found is incomplete and imperfect but workable. It is to go underneath any given political issue, whatever it may be (gun violence, immigration, gerrymandering, Russian interference), and then speak to the undergirding spiritual principles that ought to guide our lives.

5. I find politics distressing. Sometimes I just want to scream, and sometimes I just can’t seem to escape it — radio, television, internet. I’m highly motivated to make Sunday morning, in this beautiful sanctuary, a politics-free zone. A sanctuary in the old, classical sense — a holy place to escape and be safe. I will preserve that holy status until my dying day. Yet we must also speak of moral living.

6. Therefore, I try to speak of the undergirding spiritual principles. For example, the linkage, cause and effect, between our thinking and the world we create is such a principle.

I would like to share one more thought with you this morning. It comes from Charles Peguy (1873-1914), a French poet and essayist.

One thing fascinating about him is that he is quoted and beloved by the hard left and the hard right of the previous century. Quoted regularly by several liberal Swiss theologians, at the same time he was a favorite of Benito Mussolini.

“Everything Begins in Mysticism and Ends in Politics,” According to the Poet and Essayist Peguy

I think what he meant is that our experience of God — not any standard received teaching, no dogma, no catechism but rather our first-hand experience of God — ultimately informs how we then act in the world.

Our inner heart and soul and mind experience of the holy, the sacred, the divine is the ultimate energy behind how we then act and behave.

Here is what Richard Rohr, the Franciscan Priest, had to say about this:

“Transformative change in politics depends so much on having a clear view of the desired end. Where does that vision come from? Possibilities may be offered by various ideologies, or party platforms, or political candidates.

But for the person of faith, that vision finds its roots in God’s intended and preferred future for the world. It comes not as a dogmatic blueprint but as an experiential encounter with God’s love, flowing like a river from God’s throne, nourishing trees with leaves for the healing of the nations (see Revelation 22: 1-2).

This biblically infused vision, resonant from Genesis to Revelation, pictures a world made whole, with people living in a beloved community, where no one is despised or forgotten, peace reigns, and the goodness of God’s creation is treasured and protected as a gift.

Such a vision strikes the political pragmatist as idyllic, unrealistic, and irrelevant. But the person of faith, whose inward journey opens his or her life to the explosive love of God, knows that this vision is the most real of all. It is a glimpse of creation’s purpose and a glimmering of the Spirit’s movement amid the world’s present pain, brokenness, and despair.”

Conflict Management Divides into Four Categories, not All of Which Are Baneful.

Years ago, I had a rare opportunity to get some training from the Alban Institute in Washington, D.C., on what was called Conflict Management.

I envisioned, foolishly in hindsight, of potentially being a consultant to conflicted churches rather than a pastor. After all, every church I had served was in some type of conflict. I took both the basic and advanced training, and consulted with several congregations for a time.

For ease of understanding the broad spectrum of conflict, the institute divided it up into four categories:

Level I Not so bad. Two people or groups disagree on how to proceed about an issue.

Level II More than disagreement, the other group is characterized by exceptionally low IQ and deeply morally compromised. Some name calling.

Level III Reputations are ruined. Reconciliation is seen more as capitulation. The other is seen no longer as stupid, but rather clever and evil. Any hope for peace is nearly gone.

Level IV Guns (or other weapons) are involved.

Here’s the rub:

The core mistake, both in churches and in politics in general, is the view that conflict, that is all conflict, is bad.

Whereas in reality, Level I is wonderful. Genuine disagreement, yet civil and respectful, can and does lead to a third way, not initially envisioned by either group.

Quaker theologian Parker Palmer has a hopeful, but not Pollyannaish, view. He writes:

“Human beings have a well-demonstrated capacity to hold the tension of differences in ways that lead to creative outcomes and advances. It is not an impossible dream to believe we can apply that capacity to politics. In fact, our capacity for creative tension-holding is what made the American experiment possible in the first place. . . . America’s founders—despite the bigotry that limited their conception of who “We the People” were—had the genius to establish [a] form of government in which differences, conflict, and tension were understood not as the enemies of a good social order but as the engines of a better social order.”

That attitude is medicine for our times.

1) Be Careful How to Think of Others;

2) Mysticism Informs Politics;

3) Disagreement is not Bad.

Be careful how you think about others. Jesus was rather clear on the importance of this. How you think leads directly to both how you then treat and interact with others, as well as to the general health of your own soul.

Second, your mysticism informs your politics. Your experience of God, your vision of God’s world informs how you then act in the world, including how you vote.

And third, disagreement is not bad. Rather, civil disagreement can lead not just to more pragmatic solutions, not just to solutions capable of garnering enough votes, but to holier solutions, engines of a better social order.

As it said in that refrain: God help us to become what we pray.

Amen.

Download this sermon in PDF form here.

Featured Image Credit: Conflict / Duality. PD image thanks to John Hain via Pixabay.