A Sermon by the Rev. Dr. Arthur M. Suggs

Preached on the Third Sunday after Pentecost, June 10, 2018

The Lord’s Prayer Is the Best-Known Christian Scripture. It Goes Deep Inside.

Two Unitarian Universalists are arguing about religion.

The first one squares himself and mouths to the second that he is so ignorant about religion that he probably doesn’t even know the Lord’s Prayer. He puts $5 on the table and says, “I bet you $5 you don’t even know the Lord’s Prayer.”

The second Unitarian Universalist broadens his face with a grin, puffs himself up and retorts, “Oh yes, I do. ‘Jesus loves me, this I know, for the Bible tells me so.’ ”

At which point, the first Unitarian Universalist drops his shoulders and admits, “Okay, darn it. Here’s your five bucks.”

About two years ago, believe it or not, I was asked to preach on the Lord’s Prayer. Better late than never, I suppose.

This prayer is, of course, by far the best-known piece of Christian scripture ever, recited perhaps billions of times around the globe every Sunday morning.

However, being extremely well-known, it is also very easy to say it and never once think about what is being said.

The Lord’s Prayer goes deep inside us, way deep.

I was once asked to visit a church member’s father, who was in a nursing home in Syracuse. The father’s time on this earth was drawing close, and he was profoundly wrapped in Alzheimer’s dementia.

During the time I visited him, conversation was completely impossible, but every once in a while, he would mumble something way underneath his breath.

Once I leaned over him and tried to understand what he was gibbering, what the man was muttering, and it dawned on me that he was trying to recite the 23rd Psalm.

“Wow!” I thought. I mentioned that to the nurse as I was leaving. “Do you realize this guy knows the 23rd Psalm?”

She answered quickly, “Oh yes! He knows the 23rd Psalm; he knows the Lord’s Prayer; and believe it or not, he also knows the Syracuse Fight Song.”

An Accident Brings the Doxology to the Lord’s Prayer — It’s not in Jesus’ Original.

Now let me tell you some facts about the Lord’s Prayer that you might not have known. Then I also want to look more closely at a few of the lines within it.

• The Lord’s Prayer is found twice within the Bible, albeit in reduced form as we know it now.

We read the Matthew 6: 9-13 version, and then there’s a slightly shorter version in Luke 11: 2-4. It is not found in Mark or in John.

• In Matthew, the context is the Sermon on the Mount, Chapters 5 through 7, in which Jesus in this particular form is talking about praying in non-hypocritical ways, so as not to seem ostentatious or wordy or pious by others.

In other words, don’t pray in the end zone right after you’ve scored a touchdown so that you’re seen by everybody, but rather pray in your closet off your bedroom.

• In Luke, the context is the disciples asking Jesus how to pray, and JC says, “Do it this way.”

The Lord’s Prayer is original with Jesus, but only up to a point. The theme or concept in every single line of the prayer can be found in the Hebrew scriptures, in his Jewish tradition.

There are only three things generally referred to as “the Lord’s,” which would be the Lord’s Prayer, the Lord’s Supper, and the Lord’s Day.

It is probably not a coincidence that those three occasions do more to unite the global church than probably anything else.

On that one day of the week, celebrating holy communion, praying the words that he taught us, Lord’s Day, Lord’s Supper, Lord’s Prayer.

You might have noticed when Deb Miller read the Matthew version of the Lord’s Prayer in the pre-Sermon scripture reading, it didn’t have the final sentence, “For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen.”

It was not in the Luke version, either.

What happened is that the phrase, called a doxology, was added to the prayer in the Byzantine liturgy going way back to the Fourth and the Fifth Centuries.

A whole millennium later, in the early 1600’s in England, at the time when the King James Bible was being prepared for publication, the oldest manuscripts accessible to the translators of the period were from the Byzantine liturgy.

With some reason, they thought the phrase was original from Jesus himself. That’s why the scribes at the time put the doxology into the original editions of the Book of Common Prayer.

Three centuries later, translators had much earlier exegeses of the Lord’s Prayer at their disposal, and they realized that their predecessors had jumped to a conclusion and had been wrong. But by that time, the form of the prayer had been set, and it had caught on permanently. It’s a nice ending anyway.

• The 1611 insertion of the doxology in the Lord’s Prayer in England’s Book of Common Prayer occurred first.

That version was used by the Anglicans and the Episcopalians and eventually the Protestants, but not the Catholics.

The Roman Catholic Church did not add the doxology to their prayer until well past the middle of the Twentieth Century, which of course made it interesting when Protestants and Catholics worshipped together.

Toward the end of that prayer, the Catholics would look up and wonder why the Protestants were still praying even after the prayer was over. And the Protestants looked up and wondered why the Catholics stopped early and didn’t finish the prayer.

In 1969, however, the Catholics blinked first and added the doxology to their Roman Rite Mass.

Deciding the difference between using the word “debts” or “trespasses” is definitely amusing, no matter which word you choose.

You might like to try that when you’re worshipping away from your home church. Try using the wrong word on purpose. It’s always a lot of fun.

For English speakers, the word “debts” comes from a translation by John Wycliffe going back to 1395.

But then, well over a century later, William Tyndale did a translation in 1526 and decided to use the word “trespasses.”

The word in Greek, and actually in each of those two different English words as they were understood at the time, didn’t mean just financial debt or trespassing on somebody’s property.

The words mean more generally what we might call sins or offenses. There are so many ecumenical versions of the prayer that now in modern times, many churches just use the word “sins.”

Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread Winds up in a Long String of Words

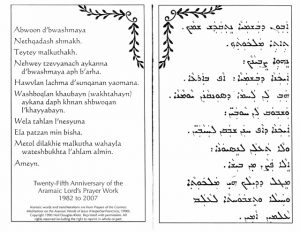

Let’s look at some portions of the Lord’s Prayer, a few of the phrases in it, but I would remind you that Jesus spoke in Aramaic.

The Aramaic version was translated into the Greek, and then the Greek was used for the English version that we’re used to.

However, I will be referencing some erudition by the Aramaic scholar, Neil Douglas-Klotz. He has at least four books out, examining the Aramaic words of Jesus. In particular, I’ll be quoting and using his book, called Prayers of the Cosmos, which looks at the Lord’s Prayer and the Beatitudes.

What I have come to learn from his research and from studying it is that this prayer is not merely practical.

It’s not just that people will need to be forgiven or will want something to eat today and every day, but rather, the Lord’s Prayer has a powerful mystical side to it, a very deep spiritual side to it, which I hope you will understand.”

Here are some examples …

Want to know just how powerful a prayer The Lord’s Prayer is intended to be … and can be? The Aramaic version holds clues.

Download or view the full sermon PDF now …

Featured Image Credit: Jesus Preaching the Sermon on the Mount

Gustave Doré. PD Wikimedia Commons.